Rethinking the Keyboard: A Journey to Ergonomic Efficiency

The Problem with Modern Typing

As a software engineer, I spend countless hours at my keyboard, coding, navigating terminals, wrestling with tmux sessions, and diving deep into neovim (btw) configurations. What started as occasional wrist discomfort when using the keyboard and mouse, aggravated by occasional tennis playing, evolved into a persistent reminder that something needed to change. The constant switching between keyboard and mouse was particularly problematic, creating repetitive strain as my hand moved back and forth throughout the day. The traditional QWERTY keyboard, designed over 150 years ago for mechanical typewriters, simply wasn’t built for the modern developer’s workflow or the mouse-heavy reliance of today’s GUI applications.

A Brief History of Keyboard Layouts

The QWERTY layout was invented in the 1870s by Christopher Latham Sholes, primarily to prevent mechanical typewriter keys from jamming by separating commonly used letter pairs. This design constraint made sense when physical metal bars needed to strike paper through an ink ribbon. However, we’ve been carrying this legacy forward through decades of technological evolution, from electric typewriters to computer keyboards, despite the original mechanical limitations being completely irrelevant.

Today’s software engineers type far more than the average office worker of the typewriter era. We’re not just typing letters; we’re constantly reaching for symbols, numbers, function keys, and modifier combinations. We navigate between applications, manage multiple terminal sessions, and perform complex text manipulations that would have been unimaginable to an 1870s typist. Yet our primary input device remains fundamentally unchanged.

The Search for Something Better

My journey toward a better typing experience led me to explore alternative keyboard layouts and ergonomic designs. I had four goals:

- Reduce physical strain: Minimize wrist extension, finger travel, and pinky overuse

- Eliminate mouse dependency: Enable a terminal-centric workflow that keeps hands on the keyboard

- Improve coding efficiency: Optimize for the symbols, shortcuts, and workflows developers actually use

- Enhance terminal productivity: Streamline interactions with tools like neovim, tmux, and command-line interfaces

In all honesty, the last three were just additional bonuses that came after the fact. But this made me realize that a setup like this could also allow me to comfortably live almost entirely in the terminal, a naturally efficient environment for developers, while minimizing the hand movement between keyboard and mouse that was contributing to my wrist issues.

This exploration culminated in a custom 36-key split keyboard layout built with ZMK firmware, specifically designed for the Corne keyboard, a compact, wireless split keyboard that represents a radical departure from traditional designs.

Key Techniques and Innovations

Home Row Modifiers

One of the most significant improvements in this layout is the implementation of home row modifiers. Instead of stretching your pinky to reach Ctrl, Alt, or Cmd keys, these modifiers are accessible directly from the home row positions. In my layout:

Sbecomes Alt when heldDbecomes Cmd when heldFbecomes Ctrl when heldJ,K, andLmirror these modifiers on the right hand

This technique eliminates the awkward pinky stretches that contribute to repetitive strain injuries while making common shortcuts like Cmd+C, Ctrl+A, or Alt+Tab feel natural and effortless.

Eliminating Pinky Travel

Traditional keyboards overwork the pinky finger, forcing it to handle everything from Enter and Shift to Backspace and various symbols. This layout redistributes that load:

- Thumb clusters: The strongest fingers (thumbs) handle Space, Backspace, Shift, and layer switching

- Reduced pinky load: Semicolon is the only primary pinky responsibility

- Balanced finger usage: More work is distributed to the stronger index and middle fingers

Layer System

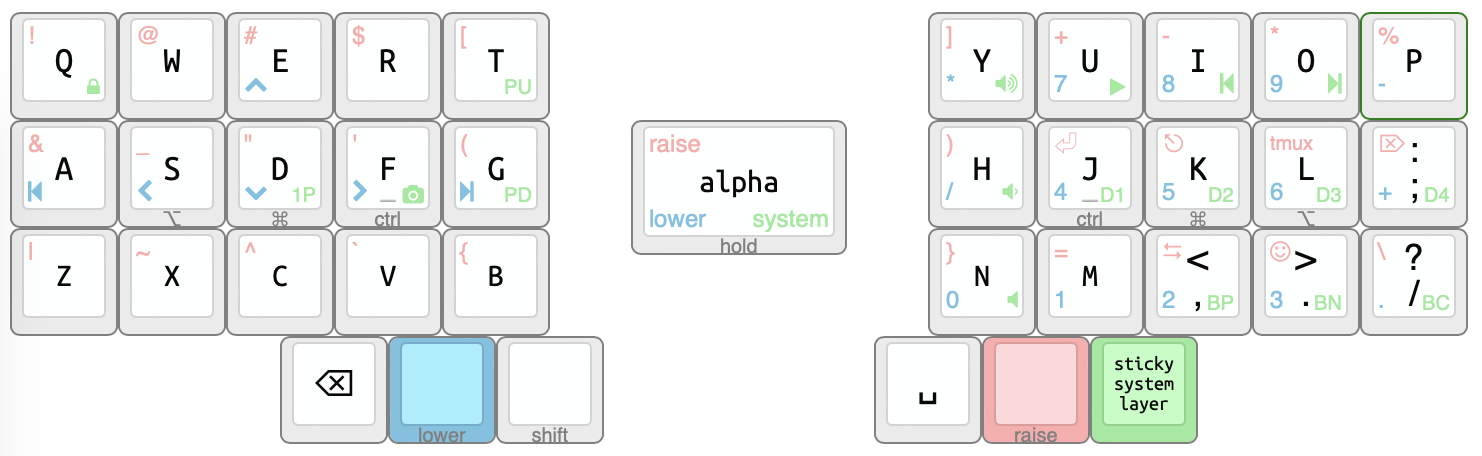

With only 36 keys, this layout relies heavily on layers—in other words, different key mappings activated by holding specific keys:

- Layer 0 (Alpha): Standard letters for typing

- Layer 1 (Symbols): Programming symbols, brackets, and special characters

- Layer 2 (Numbers/Navigation): Numeric keypad and arrow keys

- Layer 3 (System): Media controls, Bluetooth management, and macOS shortcuts

Sticky Layers

The layout implements sticky layers using ZMK’s sl (sticky layer) behavior.

This allows you to tap a layer key once and have the next keypress use that

layer, rather than holding the layer key down. It’s particularly useful for

accessing numbers or symbols without maintaining awkward finger positions.

Optimized for Developer Workflows

The layout includes specific optimizations for common developer tasks:

- tmux integration: Direct access to Ctrl+B (tmux prefix) on the symbols layer

- macOS desktop navigation: Dedicated keys for switching between virtual desktops

- 1Password integration: Quick access to password manager

- Terminal shortcuts: Easy access to common key combinations used in neovim and terminal applications

- Mouse-free navigation: Arrow keys and navigation shortcuts positioned for efficient terminal-based workflows

The Layout in Practice

The base layer maintains familiar QWERTY positioning for letters, reducing the learning curve. However, everything else is optimized for efficiency:

The symbols layer (L1) places frequently used programming characters in logical positions, while the numbers layer (L2) provides a traditional numpad layout alongside navigation arrows. The system layer (L3) handles media controls and system functions.

Results and Reflections

After months of using this layout, the benefits are clear:

- Reduced wrist strain: No more reaching for distant keys, awkward pinky stretches, or constant keyboard-to-mouse transitions

- Mouse-free productivity: Living in the terminal has become not just possible but genuinely more efficient than GUI alternatives

- Improved typing speed: Once muscle memory developed, common programming tasks became noticeably faster

- Better workflow integration: Seamless interaction with terminal tools and development environments

- Wireless freedom: The split design and wireless connectivity provide unprecedented flexibility in positioning

The transition wasn’t without challenges. The initial learning curve required patience and deliberate practice. Muscle memory built over decades doesn’t change overnight. However, the long-term benefits, both in terms of comfort and efficiency, have made this exploration worthwhile.

Looking Forward

This keyboard layout represents more than just a different key arrangement; it’s a fundamental rethinking of how we interact with our computers. As software development continues to evolve, our tools should evolve with it. The typewriter-era constraints that shaped QWERTY are long gone, but the possibilities for optimization are just beginning to be explored.

For developers experiencing discomfort with traditional keyboards, or those simply curious about optimizing their workflow, alternative layouts like this offer a compelling path forward. The initial investment in learning pays dividends in comfort, efficiency, and long-term hand health.

The future of typing doesn’t have to be constrained by the past. Sometimes, the best way forward is to start from scratch and build something better.

That Sounds Great, Where Do I Start?

If all that sounded like a good idea to you, the best way to start is getting a pre-assembled Corne keyboard (or similar). I would strongly recommend typeractive—the quality is above most stores out there. If it looks pricey… that’s probably because it is, however keep in mind that these are all custom-made keyboards, made with high-grade switches, keycaps and 3D-printed cases.

You can also go the route of assembling everything yourself, but unless you’re up for the challenge and/or enjoy electronics I wouldn’t recommend it, at least to begin with; you’re not going to save that much money anyway.

This layout is open source and available on GitHub. The configuration uses ZMK firmware and is designed for the Corne keyboard, though the concepts can be adapted to other split keyboards.